|

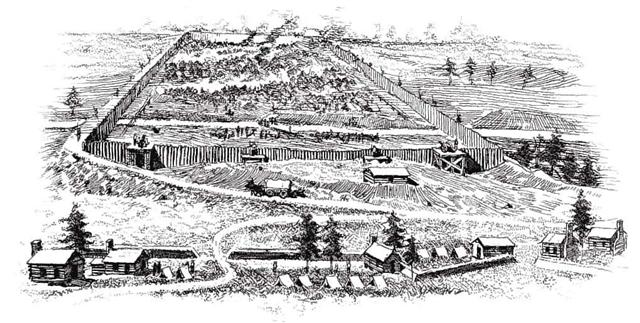

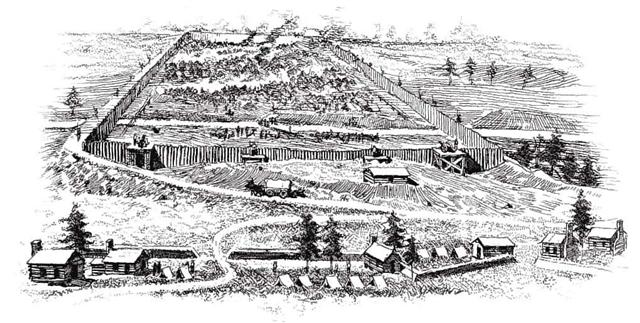

The Prison Pen at Florence, South Carolina.

|

The stockade at Florence was so similar to the one at Andersonville that it needs but little description. It inclosed about eight acres, upon the two slopes of a valley through which ran a large stream of water of six times the volume of the one at Andersonville. This stream was ordered upon both sides by a swamp comprising about two acres, which in wet weather was almost impassable. At such times it was necessary to wade above the knees in the black swamp muck in order to reach the stream to procure water. Much of the time during the winter the frost was an inch deep and ice formed over the stream, but never, I think, sufficiently thick to bear one's weight. The ice rendered the wading very disagreeable; besides, few possessed dishes or cups that would hold over a pint or quart.

During the winter hundreds of starved, half-naked, emaciated prisoners stood at the edge of the swamp, with their trousers tucked up to their hips, or, in many instances, without any at all, soliciting the job of filling the cups of those in want of water, for a quid of tobacco, a mouthful of food, or a stick of wood.

Very soon after my arrival within the stockade I clubbed my all together with James B. Snow and Frank K. Bonney, who had preceded me but a few days. Aside from what we had upon our backsóand Snow and Bonney were no better clothed than Iówe mustered a dilapidated army blanket; a regulation overcoat worn very thin and rotten; three haversacks; one canteen; two tins used for plates, made by splitting a canteen; one tin cup that held a quart; one pail, holding about two quarts, roughly made from old tin that had once done service upon the roof of a baggage car; one case knife; one iron spoon; an apology for a jack-knife; and one tobacco pipe.

The nights were growing very cold, and we had already experienced a cold storm of several days' duration without any shelter. Many had burrowed into the ground from the hill-side, covering their burrow with a blanket; but we decided that our shelter must be on the top of the ground if we wished to live.

It required one full week to finish the shelter, which, except the roof, was built of mud from the swamp. This swamp muck had considerable clay mixed through it, and when baked dry in the sun it would retain its form very well, and even withstand much wetting before it would break down. We brought this mud from the swamp in our hands, about one hundred yards, to the site selected for our building, mixing it to the proper consistency at the swamp, so that it was ready to add to the walls as soon as brought.

It was necessary to build slowly, that one layer of mud might dry to a certain extent be-fore another was added. The molding was all done with the hands, and the mud pressed as compactly as possible. We built the walls about ten inches thick and three feet high to the eaves, while the gable ends brought the ridge five feet from the ground. Its size had to be such that the woolen blanket would cover it as a roof. This gave us a hut about six feet long and four feet wide inside. One end, facing the south, was about half taken up with a mud chimney built about seven feet high, leaving the remainder for an entrance. The chimney furnished us with a fireplace about twenty inches square. Snow, Bonney, and myself occupied this mud hut for two months. It sheltered us from the cold, but eternal vigilance was necessary to keep it even comparatively dry during stormy weather.

About the time it was finished I managed to get out one day on the regular detail sent for wood, and I brought back the overcoat stuffed full of pine needles, which were spread upon the ground for bedding. When the weather was very cold, the overcoat was used to close the opening left by the side of the chimney. It was a snug, comfortable nest in dry weather, even without a fire; though much of the time we managed to obtain wood so that a fire of splinters could be kept going I during the long, cold evenings.

visits since _____.

Page updated

05/25/2006